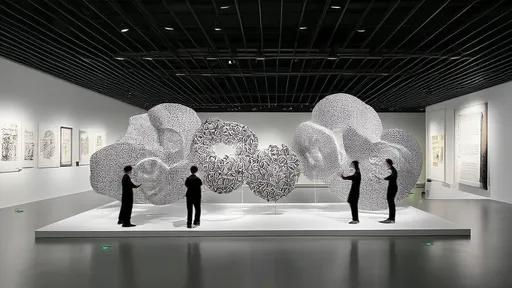

Against the limestone peaks that have inspired poets for centuries, a new artistic dialogue is unfolding in Guilin. The Guilin Art Festival, with its thematic focus "Symbiosis of Nature and Art," presents a compelling case study in how contemporary art can engage with ancient landscapes without disrupting their inherent poetry. What emerges from this year's Fine Arts Section is not merely art placed in nature, but art that breathes with the landscape, creating what curators are calling "site-specific aesthetic practice."

The festival's artistic director, Liang Weimin, describes the approach as "listening to the mountains." He explains how artists spent months living in Guilin's rural communities before creating their works. "We didn't want artworks that simply used the landscape as backdrop," Liang notes. "We sought creations that would emerge from the land itself, that would speak with the rivers and whisper with the bamboo forests." This philosophical foundation has resulted in one of the most integrated art experiences in recent Chinese contemporary art history.

Walking through the exhibition areas, visitors encounter Yang Jian's "Karst Memory" – not a sculpture placed before the mountains, but rather a series of subtle interventions within the landscape itself. Using locally-sourced limestone fragments and traditional masonry techniques, Yang has created pathways that appear to grow organically from the terrain. "The work isn't about adding something new," the artist reflects. "It's about revealing what was always there, helping people see the landscape with fresh eyes."

Meanwhile, along the Li River, Chen Lili's "Water Calligraphy" installation uses biodegradable pigments that flow with the current, creating temporary patterns that change with the water's mood. Local fishermen have become unexpected collaborators, with some incorporating the floating colors into their daily routines. "At first, we thought it was strange," says fisherman Huang Desheng, who has worked the river for forty years. "But now I find myself watching how the colors dance with the water, how they look different in morning mist versus afternoon sun. It makes me see my river anew."

The integration extends beyond visual art to encompass sound and movement. Composer Zhang Wei created "Bamboo Symphonies" using hollow bamboo poles of varying lengths, hung throughout a bamboo forest. The wind plays the installation, producing different tones depending on weather conditions. During my visit, a light drizzle created a percussive accompaniment to the wind's melody. "This isn't music composed by humans," Zhang observes. "It's music composed by nature, with humans merely providing the instruments."

Local materials and traditional craftsmanship feature prominently throughout the festival. Weaver Yang Hongxia has created massive textile works using natural dyes made from Guilin's indigenous plants – turmeric yellow, indigo blue, and mineral reds from local clay. Her installations drape between trees like colorful spiderwebs, fluttering in the mountain breeze. "Every thread contains the story of this place," Yang says, running her fingers through a deep blue fabric. "The plants, the water, the minerals – they all become part of the artwork."

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the festival is how it has engaged local communities. Rather than being passive spectators, villagers have become active participants in the creative process. In Yangshuo County, elderly residents who have practiced paper cutting their entire lives collaborated with contemporary artists to create large-scale installations that adorn traditional courtyard homes. The resulting works blend centuries-old folk art with modern aesthetic sensibilities.

Farmer and part-time artist Qin Haolong expresses what many locals feel: "At first, we didn't understand why city artists wanted to make art here. But now we see they're not changing our home – they're helping us remember why it's special." His own contribution – a series of sculptures made from farming tools and natural materials – stands as testament to this evolving relationship between local tradition and contemporary practice.

The festival's educational programs have further deepened this connection. Daily workshops teach visitors about Guilin's ecological systems, traditional building methods, and conservation efforts. Children from nearby schools participate in "nature drawing" classes where they learn to observe the landscape with an artist's eye. "We're not just creating art for today," explains education director Wang Liling. "We're nurturing the next generation of stewards for this precious landscape."

As dusk settles over the karst peaks, the artworks transform with the fading light. Solar-powered installations begin to glow with soft luminescence, while sound pieces take on new character in the evening quiet. The night program includes performances that use the natural landscape as both stage and protagonist, with dancers moving through bamboo groves and musicians playing from boats on the river.

Critics have noted the festival's significance extends beyond the art world. Environmental scientists praise the event's minimal ecological footprint and emphasis on conservation. Sociologists observe how it has revitalized rural communities while maintaining cultural continuity. As Professor Elena Martinez from Barcelona University, who specializes in art and ecology, comments: "What's happening in Guilin represents a paradigm shift in how we conceive of art in natural settings. This isn't land art – it's land conversation."

The challenges of creating art in such sensitive environments haven't been insignificant. Artists had to work within strict environmental guidelines, with every material and process vetted by ecological experts. The resulting constraints, however, often sparked greater creativity. Installation artist Liu Bowen notes: "When you can't drill into rock or introduce foreign materials, you start thinking differently. You learn to work with what the land offers you."

As the festival enters its final week, the question of legacy arises. Unlike traditional exhibitions where artworks get packed away, many pieces here will remain, slowly returning to the earth. Chen Lili's river pigments will fade, Yang Jian's stone paths will weather, and Zhang Wei's bamboo instruments will eventually decompose. This impermanence, curators argue, is central to the festival's philosophy.

"We're challenging the notion that art must be permanent to be meaningful," says chief curator Zhang Xiaogang. "The most beautiful things in nature are transient – cherry blossoms, morning mist, falling leaves. Why shouldn't art embrace this quality?"

For visitors, the experience remains profoundly moving. Shanghai architect Li Na, visiting with her family, captures the sentiment many express: "I came expecting to see art in nature. Instead, I found nature revealed through art. The mountains look different to me now – more alive, more conscious. I'll never experience landscape the same way again."

As the Guilin Art Festival demonstrates, the most powerful art may not be that which stands against nature, but that which learns to speak nature's language. In the dialogue between karst peaks and human creativity, both emerge transformed, offering a vision of how we might inhabit this earth more gently, more beautifully, more consciously. The festival continues through the end of the month, though its impact on both artists and audience promises to endure much longer.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Oct 24, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By James Moore/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025