In the quiet corners of Beijing's 798 Art District, a subtle revolution is unfolding. While digital screens dominate global communication, Chinese paper-based art is experiencing an unprecedented international renaissance. The journey from traditional paper media to clustered global networks represents one of the most fascinating cultural transformations of our time.

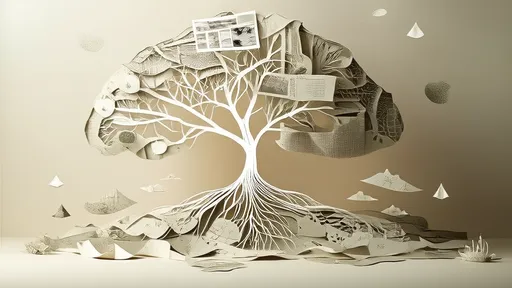

The story begins with what cultural historians call the "paper memory" of Chinese civilization. For centuries, paper served not merely as a medium but as a cultural DNA carrier. The tactile relationship between Chinese artists and paper differs fundamentally from Western traditions. Where Western artists often treat paper as a surface to be filled, Chinese creators engage with paper as a living entity—its texture, absorbency, and resilience become active participants in the artistic dialogue.

Traditional paper arts were once considered fragile artifacts destined for museum vitrines. The conventional wisdom held that xuan paper, rice paper, and other traditional mediums couldn't survive the journey across cultural boundaries. Yet something remarkable has occurred in the past decade. Rather than diminishing in the digital age, paper art has discovered new relevance precisely because of its material authenticity in an increasingly virtual world.

The transformation began with what I've termed the "mediation moment." Around 2015, Chinese paper artists started collaborating with international curators in ways that fundamentally recontextualized their work. Instead of presenting paper art as exotic artifacts, these collaborations positioned them as contemporary responses to global issues—environmental concerns, the crisis of materiality, and the search for authentic human connection in digital spaces.

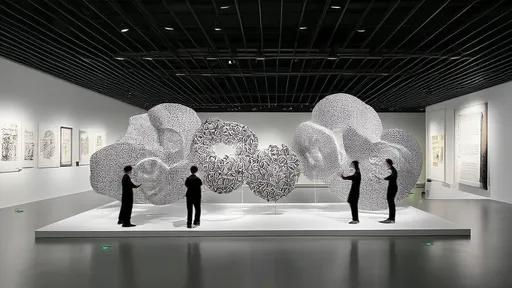

What makes the current movement distinctive is its networked character. Earlier attempts at internationalizing Chinese paper art followed what scholars call the "lone masterpiece" model—individual works traveling to foreign exhibitions. The contemporary approach operates through what I call "creative clusters"—interconnected networks of artists, galleries, academic institutions, and digital platforms that move together through the global art ecosystem.

These clusters function as cultural ecosystems rather than mere exhibition circuits. When the "Breathing Paper" exhibition traveled from Shanghai to London then to New York, it wasn't just artworks crossing borders. The entire creative environment traveled with it—master paper makers conducting workshops, scholars presenting research, and even the specific humidity-controlled environments necessary for preserving delicate works. This holistic approach has revolutionized how paper art communicates across cultures.

The digital layer has become crucial to this clustered approach. While this might seem paradoxical for paper-based art, the relationship is more complementary than contradictory. Social media platforms, virtual exhibitions, and digital archives don't replace the physical experience of paper art—they amplify its reach and create what one curator called "digital longing" for the tactile original. Instagram posts of intricate paper cuttings generate interest that drives physical attendance at exhibitions halfway across the world.

International collectors have developed what gallery owners describe as "paper literacy." A decade ago, Western collectors often approached Chinese paper works with uncertainty about preservation and valuation. Today, through cluster education programs and transnational dialogue, collectors have developed sophisticated understanding of different paper types, conservation techniques, and cultural contexts. This educated collector base has created sustainable market conditions that support artists' international careers.

The academic world has played an unexpected role in this transformation. University art departments from London to Sydney have established dedicated Chinese paper art research centers. These aren't merely study facilities—they function as network nodes that connect artists, theorists, and practitioners across continents. The academic validation has provided intellectual framework that helps international audiences understand paper art beyond superficial exoticism.

Perhaps the most fascinating development has been the emergence of what artists call "paper diplomacy." In an era of geopolitical tensions, paper art has become a subtle medium for cultural exchange that operates beneath political radar. The material itself—fragile yet enduring, local yet universal—becomes metaphor for the kind of connections possible between cultures. Several major international paper art collaborations have proceeded even during periods of diplomatic frost between governments.

The environmental dimension has added another layer of relevance. Contemporary Chinese paper artists have increasingly engaged with ecological themes, using traditional techniques to comment on modern environmental challenges. This thematic convergence has created natural bridges to international audiences concerned with sustainability and material ethics. The very process of making paper—from plant to finished product—becomes part of the artistic narrative.

Looking at specific success stories reveals the mechanism of this clustered approach. Artist Liu Jianhua's paper installations, for instance, achieved international recognition not through isolated exhibitions but through a carefully orchestrated network strategy. His work appeared simultaneously in museum exhibitions, academic publications, environmental conferences, and digital platforms—each context reinforcing the others. This multidimensional presence created what market analysts call "cultural critical mass."

The infrastructure supporting this internationalization has evolved dramatically. Specialized shipping companies now offer climate-controlled transport specifically for paper artworks. International insurance markets have developed sophisticated valuation models. Translation services specializing in art terminology ensure that conceptual nuances survive linguistic transitions. This supporting ecosystem, while invisible to most viewers, forms the backbone of successful cross-cultural transmission.

Younger generation artists are pushing the boundaries even further. Where their teachers might have hesitated to modify traditional techniques, contemporary creators freely experiment while maintaining philosophical connections to paper's cultural heritage. We're seeing paper combined with light installations, soundscapes, and even augmented reality—all while preserving the essential material dialogue that defines the tradition.

The market evolution has been equally remarkable. Auction houses that once relegated paper works to minor categories now stage dedicated paper art sales. Pricing structures have matured, reflecting not just aesthetic value but historical significance, technical innovation, and conservation status. This market sophistication provides economic sustainability that enables artists to pursue ambitious international projects.

Critical reception has shifted accordingly. International art critics who might previously have focused on exotic elements now engage with paper art through multiple theoretical frameworks—material culture studies, environmental philosophy, post-digital theory. This intellectual engagement elevates the conversation beyond cultural tourism to genuine cross-cultural dialogue.

The COVID-19 pandemic unexpectedly accelerated certain aspects of this internationalization. While physical exhibitions paused, digital clusters flourished. Online workshops connected master paper artists with international students in ways that would have been logistically impossible before. Virtual reality exhibitions allowed viewers to examine paper textures with digital magnification that revealed details invisible to the naked eye. These digital adaptations have become permanent features of the international paper art landscape.

As we look to the future, the trajectory suggests even deeper integration. We're seeing the emergence of what might be called "transcultural paper"—works that draw from multiple paper traditions while maintaining distinctive Chinese characteristics. This isn't cultural dilution but rather enrichment through dialogue. The clusters are expanding to include paper artists from Japan, Korea, Europe, and the Americas, creating truly global conversations about this most ancient of mediums.

The journey from isolated paper media to interconnected clusters represents more than just an art world trend. It demonstrates how traditional cultural forms can achieve global relevance without sacrificing their essential character. The success of Chinese paper art internationally offers a model for other cultural traditions seeking meaningful global engagement in the digital age.

In the final analysis, the internationalization of Chinese paper art succeeds precisely because it honors paper's materiality while embracing contemporary networks. The delicate balance between tradition and innovation, between local character and global language, creates the conditions for genuine cross-cultural communication. As one veteran artist told me, "Paper remembers—but it also imagines." This capacity for both memory and imagination explains why paper, against all predictions of its demise, has become a vibrant medium for international dialogue.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Oct 24, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By James Moore/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025