In the hushed galleries where classical Chinese landscape paintings whisper tales of mist-shrouded mountains and meandering rivers, a quiet revolution is unfolding. The journey from One Hundred Li of the Li River to Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains represents more than mere geographical transition—it embodies the evolving soul of Chinese landscape art as contemporary artists reinterpret centuries-old traditions through modern sensibilities.

The One Hundred Li of the Li River, a monumental scroll painting by Huang Binhong, captures the ethereal beauty of Guangxi's karst landscape with breathtaking precision. Created in the 1950s, this masterpiece exemplifies the traditional Chinese approach to landscape—where nature exists not as mere scenery but as a living, breathing entity imbued with philosophical significance. The painting's rhythmic brushstrokes and masterful use of ink wash create a world where mountains emerge from mist like memories materializing from dreams, where the Li River flows not just through physical space but through the corridors of cultural consciousness.

What makes Huang's work particularly relevant to contemporary reinterpretation is its spiritual dimensionality. The artist didn't merely depict what his eyes perceived; he captured what his heart felt and his mind contemplated. This emotional and intellectual engagement with landscape provides the foundational philosophy that contemporary artists are now building upon, transforming traditional approaches into something both familiar and startlingly new.

Meanwhile, Zhao Mengfu's Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains, created during the Yuan Dynasty, represents another pivotal reference point in this artistic evolution. Unlike the dramatic verticality of many Song Dynasty landscapes, Zhao's composition embraces a horizontal expanse that feels almost modern in its cinematic quality. The painting's subdued color palette and more personal, intimate scale marked a significant departure from the monumental traditions that preceded it, suggesting that landscape could serve as both spiritual conduit and personal expression.

Contemporary artists working with landscape traditions find themselves navigating between these two poles—the monumental and the intimate, the universal and the personal. What emerges in their work is not mere imitation of past masters but rather a profound dialogue across centuries. They employ traditional materials—ink, brush, rice paper—while infusing them with contemporary concerns about environmental change, urbanization, and the very nature of perception in an increasingly digital world.

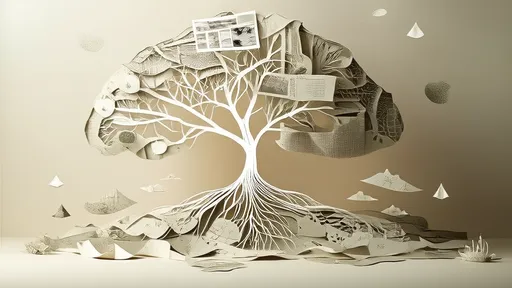

In studios from Beijing to New York, artists like Xu Bing and Liu Dan have pioneered approaches that honor tradition while radically expanding its possibilities. Xu's Landscript series, for instance, transforms Chinese characters into mountain forms, creating landscapes that are simultaneously textual and visual, ancient and avant-garde. The works challenge viewers to reconsider the relationship between written language and depicted nature, between cultural coding and pure visual experience.

Liu Dan, by contrast, approaches tradition with breathtaking technical mastery while introducing conceptual frameworks that would have been unimaginable to painters of previous generations. His monumental rock formations, rendered with almost supernatural precision, become meditations on time, erosion, and the persistence of cultural forms amid constant change. When viewing his works, one senses the ghost of Song Dynasty masters looking over his shoulder, not as restrictive presences but as collaborative spirits.

The technological revolution has further expanded the possibilities for traditional landscape's contemporary reinvention. Digital artists now create immersive installations where viewers don't just look at landscapes but enter them virtually. Algorithmic art generates mountain ranges based on classical principles but through computational processes. These developments raise fascinating questions about authenticity, tradition, and the nature of artistic creation itself.

Yet for all these technological innovations, the heart of the tradition remains remarkably resilient. The fundamental concepts of qi yun (spirit resonance) and the harmonious balance between humanity and nature continue to inform contemporary practice, even when the resulting works bear little superficial resemblance to their classical predecessors. This suggests that what defines Chinese landscape art is not any particular style or technique but rather a particular way of seeing and being in the world.

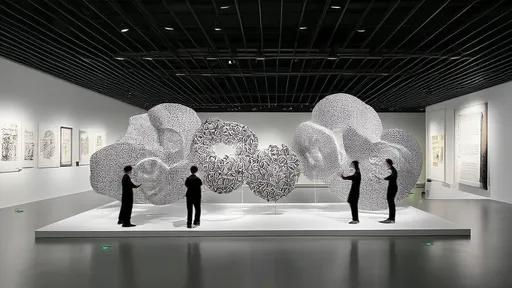

Gallery exhibitions increasingly highlight this continuum between past and present. Curators deliberately hang contemporary reinterpretations alongside classical masterpieces, creating visual conversations that transcend chronological boundaries. Viewers witness how a 21st-century artist's response to industrial pollution engages with an 11th-century monk's meditation on mountain solitude, recognizing that both emerge from the same fundamental human impulse to find meaning in nature's forms.

The commercial art world has taken note of this vibrant tradition-meets-innovation movement. Auction houses report growing interest in contemporary works that demonstrate deep engagement with classical landscape traditions, particularly when those engagements produce something genuinely new rather than merely nostalgic. Collectors seem to recognize that the most exciting developments often occur at intersections—where ancient techniques meet modern concerns, where scroll formats encounter installation art, where Chinese sensibilities converse with global perspectives.

Academic institutions have likewise expanded their curricula to explore these intersections. Art history departments that once treated traditional Chinese landscape as a closed chapter now examine its ongoing evolution. Studio programs teach classical brush techniques alongside digital tools, encouraging students to understand tradition not as limitation but as foundation. The most promising young artists emerging from these programs demonstrate remarkable ability to move fluidly between historical reference and contemporary expression.

What becomes clear when tracing the path from One Hundred Li of the Li River to Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains and beyond is that Chinese landscape painting was never meant to be a static tradition. Its greatest masters were themselves innovators who reinterpreted what came before them. The contemporary artists now expanding this vocabulary are therefore not breaking with tradition but fulfilling its deepest purpose—to remain vitally connected to the present while honoring the wisdom of the past.

As environmental concerns intensify globally, the philosophical underpinnings of Chinese landscape art feel increasingly relevant. The tradition's emphasis on harmony between humanity and nature, its recognition of landscapes as living systems rather than passive scenery, its profound spiritual dimension—all these elements resonate with contemporary ecological awareness. In this sense, the reinvention of traditional landscape painting represents not just an artistic development but a cultural resource with potential significance far beyond gallery walls.

The journey continues. With each brushstroke that acknowledges past masters while speaking in a contemporary voice, with each exhibition that bridges historical divides, with each young artist who discovers personal expression through ancient forms, the tradition renews itself. The mountains and rivers that flowed through Huang Binhong's One Hundred Li of the Li River and Zhao Mengfu's Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains continue their course through the imagination of artists working today, their waters enriched by new tributaries, their peaks illuminated by new light.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Oct 24, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By James Moore/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025